Introduction:

Usage:

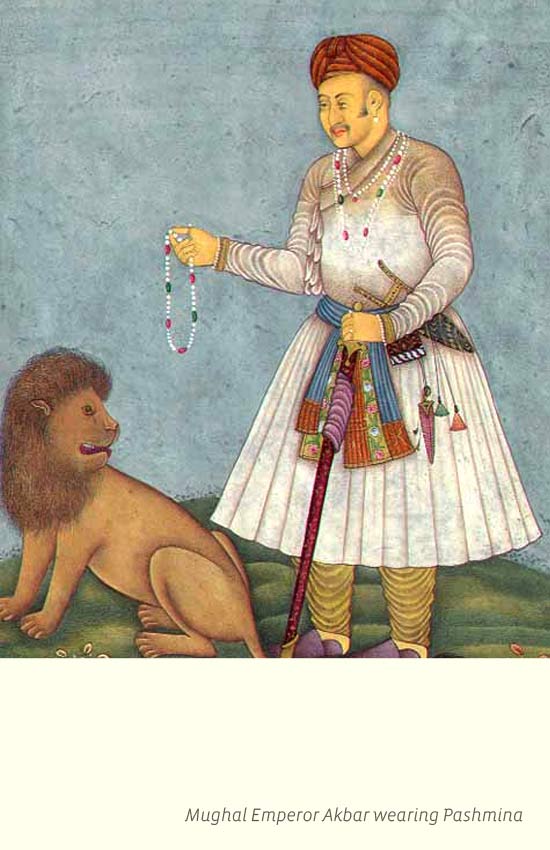

When Pashmina shawls began to be woven in the Jammu and Kashmir and Ladakh regions, they were essentially for the royalty. Pashmina was considered the ‘gold’ fibre and was worn only by the king’s family and was highly patronized by the Mughals, especially, Akbar.

These shawls have also been used in trade all over the world, India being the only highest exporter of pashmina in the world for a long time. From the 19th Century, pashmina has been in high demand as ‘cashmere’ all over the world and even the exorbitant prices have never been an obstacle in the sale of these luxury shawls.

Significance:

It has been an object of desire for Mughal emperors and Sikh maharajas, Iranian nobles, French emperors, Russian and British aristocrats and eventually for the increasingly prosperous bourgeoisie created on both sides of Atlantic by the industrial revolution.

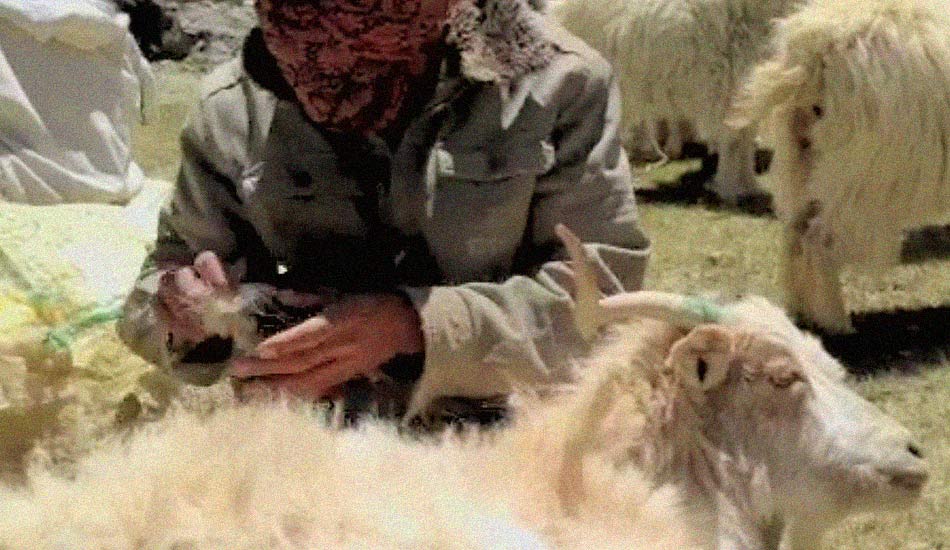

Found in the snows and Hills of Himalayas, this wool comes from the Goat called Pashmina or ‘Changthangi’. This breed of Goat is found in Ladakh and Kashmir, usually raised for Meat or Cashmere/Pashmina Wool. The Pashmina Goat survives on the Grass grown on the lands of Kashmir and Ladakh where the temperature can go as below as -30 Degree Centigrade. Changthangi Goat sheds an approximate of 3 – 8 ounces of wool/ winter coat every spring. This wool is then collected and used for making Pashmina Shawls.

Myths & Legends:

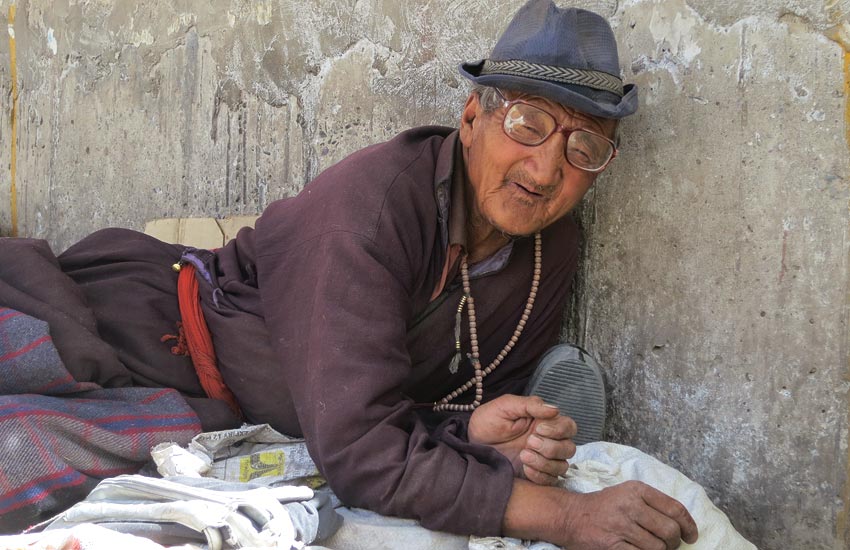

In Ladakh, it is said that wool or pashmina has compassion because it eases man’s suffering regardless of whether he is a king, queen or shoe maker, wool serves the same purpose for everybody. The shawl weaving industry of Kashmir is as old as its hills.

“It is to be believed that the industry flourished in the days of the ‘Kauravas’ and ‘Pandavas’ (Mahabharata) and that the shawls of Kashmir reached as far as Rome wherein, they adorned the local beauties particularly those in the Caesar’s court.

Syed Ali Hamadani, who introduced Islam in Kashmir, brought with him nearly 700 pious and saintly disciples mostly artisans and craftsmen – who were spread all over the valley, not only to popularize Islam as a faith, but also to teach and train the local people in the making of various arts and crafts, which would one day be world famous. His arrival in Kashmir was the beginning of a total & complete revolution, encompassing all aspects of life in the valley, and its requirements – social, economic & cultural.”

“It is said that, once the Saint was asked how the womenfolk could be gainfully employed & his reply was, that “Moon”(wool) would come from the eastern side of the mountain (Eastern-Ladakh), which would provide a livelihood to the locals especially, the women folk who would contribute very significantly to the growth of the art, as it would involve a great deal of spinning and weaving. It is believed to be blessed pursuit to the people throughout, after the tradition of Fatima, the beloved daughter of the prophet of Islam, was given a spinning wheel on the occasion of her marriage as a part of her dowry.”

History:

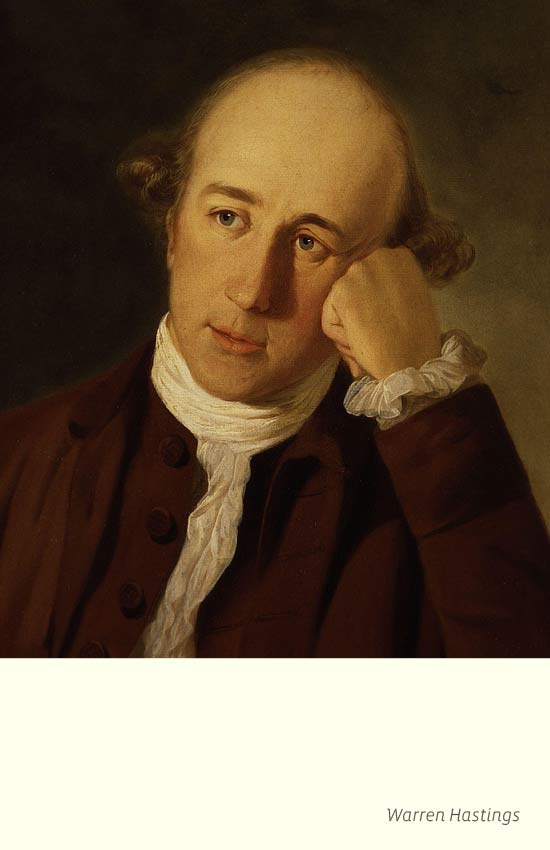

Till 1959, pashmina of western Tibet was exported to Kashmir through Ladakh. : Ladakh and Kashmir had sole monopoly over the purchase of pashmina from west Tibet under an agreement of 1684 concluded between Tibet independent and Mughal Kashmir. Pashmina has a long chequered history. British India was very keen to import pashmina from western Tibet and Ladakh. In this connection, British India’s governor general Warren Hastings had deputed George Bogle to Tibet on a political and trade-mission. Lord Dalhousie, another governor general conceived a great project to build Hindustan-Tibet highway to encourage and accelerate the flow of pashmina between the Gartok area of Tibet and British India territory.

Pashmina shawls were freely available in St. Petersburg than capital of Russia in the 1790’s. The pashmina shawl reached west Asia be sea and land routes. At certain times, the use of rashes of pashmina material was confined to princess and a few other great noblemen by the special permission. In Iran Royal edicts purporting to have at least limit, the use of pashmina shawls in the interest of encouraging Iranian industry seem to have ineffective.

Gilman’s agent was followed by British official William Moorcroft, who visited Gostok in 1812 in disguise as a gosain to buy pashmina. Moorcroft persuaded Garpon, the governor of Gastok to sell some quantity of pashmina at an exorbitant cost. The secret deal between Garpon and the British officer leaked out. The Garpon was taken to Lhasa in Chains and sentenced to 3 years imprisonment.

The Dogra general took stringent action to crush the export of pashmina to Rampur and Bashahr of Himachal Pradesh and five traders of region were excented and several other traders were imprisoned. In 1890, an Englishman john Gilman sent an agent to Gartok, summer headquarter of west Tibet to explore avenues for importing pashmina in British India. He bought a pashmina goat and a shawl. The Ladakhi ruler strongly protested against this and the governor of Gartok was punished by the Tibetan govt. Kashmir has been manufacturing shawls for centuries. In the second quarter of 19th century there were 40 thousand to 45 thousand weavers and one-lakh spinners in Kashmir valley on an average one-lakh pieces of pashmina shawls were manufactured annually. Of these 80 thousand were exported to Europe, Iran, Magnolia, Russia, Central Asia, Asalica, Turkey, Africa and Other parts of India.

Tradition says that the transparent veil worn but the Monalisa is in reality one of the earlier pashmina fabrics that could be drawn through a lady’s ring as a test of fineness.

According to Ain-I-Akbari, Mughal king, Akbar the great encourage in every possible way the manufacture of shawls in Kashmir, Akbar coined a new name for pashmina as Paremnarm meaning supremely soft. The custom of presenting shawls is also recorded in the rage of Shah Jahan.

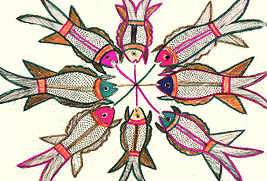

Design:

Most of the Pashmina Shawls have only one colour throughout. However, there are varieties of Pashmina Shawls which are being woven these days – pure pashmina, pure ring pashminas, silk blended pashminas, two tone pashminas, ombre/gradient pashminas, pashmina with furs, beaded pashmina, aristocrat pashmina and brides pashmina.

Though most of the Pashmina, which are sold in the market, are of pure wool, still for those who cannot afford the high ranges of Pure Pashmina, can go for Viscous Pashmina. Viscous Pashmina have a blend of Viscous, which is an artificial silk look giving agent. However, one should avoid buying these, as the Viscous does not have the warmth, which pure wool has. The Price range of Pashmina Shawl begins from Rs 4000/ – and can go as high as Rs 20,000. The very high ranges can be for bedsheets and curtains made out of pure Pashmina found only in Kashmir and Ladakh.

The value addition of pashmina shawls is being done by designing and embroidery work, which is highly scarce in the Ladakh region. Pashmina shawls are mainly dyed in various natural colours for embellishment. The Ladakhi pashminas do not have any intricate designs or motifs. The weavers’ here work around the various twill weaves: herringbone twill, pointed twill, plain twill, basket twill etc. The shawls in the Ladakh region are usually loosely woven and the weaves are very distinct, creating beautiful patterns as embellishments.

Shahtoosh Shawls, the legendary ‘ring shawl‘ is incredible for its lightness, softness and warmth. The astronomical price it commands in the market is due to the scarcity of raw material. High in the plateaux of Tibet and the eastern part of Ladakh, at an altitude of above 5,000 meters, roam Pantholops Hodgosoni or Tibetan antelope. During grazing, a few strands of the downy hair from the throat are shed and it is these, which are painstakingly collected until there are enough for a shawl. Yarn is spun either from shahtoosh alone, or with pashmina, bringing down the cost somewhat. In the case of pure shahtoosh too, there are many qualities-the yarn can be spun so skilfully as to resemble a strand of silk. Not only are shawls made from such fine yarn extremely expensive, they can only be loosely woven and are too flimsy for embroidery to be done on them. Unlike woollen or Pashmina shawls, Shahtoosh is seldom dyed; its natural colour is mousy brown. To get this fibre, the goats have to be killed and hence, with time, the government banned the making of these shawls.

Challenges:

The pashmina industry of Ladakh is not as commercialised as its counterpart in Kashmir and since it is made for local consumptions, the industry in Ladakh does not face much challenges. Their technique is authentic, raw materials are natural and the product has not changed in today’s times.

Introduction Process:

Raw Materials:

Pashmina fibre of Ladakh: It is obtained from the winter undercoat of a variety of a domestic goat, which is known as pashmina goat. It is recognized as a luxury fibre and commands some of the highest prices in the world of textiles, because of extreme softness, elegance and lustre. The growth of pashmina is stimulated by the intense winter cold of windswept plateaus situated at high altitudes of ‘Changthang’ in Ladakh. Pashmina goats are sturdy, short-necked, medium in size and adapted to the migratory life under different conditions. The average production of pashmina of an adult male is 224gms. Female yields more pashmina than male.

Natural dyes: Indigo (blue), annota seeds (red), henna and myrobolan (shades of yellow and brown).

Mordents: Aluminium sulphate and ferrous sulphate

Fabric softeners: Eulon etc.

Fragrance micro-capsules: for aroma finishing of shawls.

Tools & Tech:

Looms: Pashmina shawls are wither woven on back-strap looms or on pit-looms, in Ladakh. Both these looms are easily transportable, since nomads who also rear pashmina goats make these. The looms require little wood and are usually tied for support to the ground or the weaver’s back. The nomad communities themselves make these looms and hence are easily rebuild able

Combs: Combs are required for de-hairing before the spinning of the pashmina yarn takes place.

Charkha: They use the charkha for spinning yarn.

Rituals:

process:

Pashmina is one of the finest of wools and very warm, Ladakhi people are rich in having the kind of wool called Pashmina, which weave shawls and other outfits from this extra ordinary product.

The Wool for Shawls is shed by the Pashmina Goats. In the Spring Season, the goats shed their outer cover for the new skin to come. The weavers then collect these. The weavers then make a distinction of very pure and pure wools. These are then woven on Kargha (the winding machine or the pit-loom). The designs and patterns are decided and then the weaving is done. Once the weaving is complete these are then dipped in natural colours, made from flowers to give different colours to the Shawls.

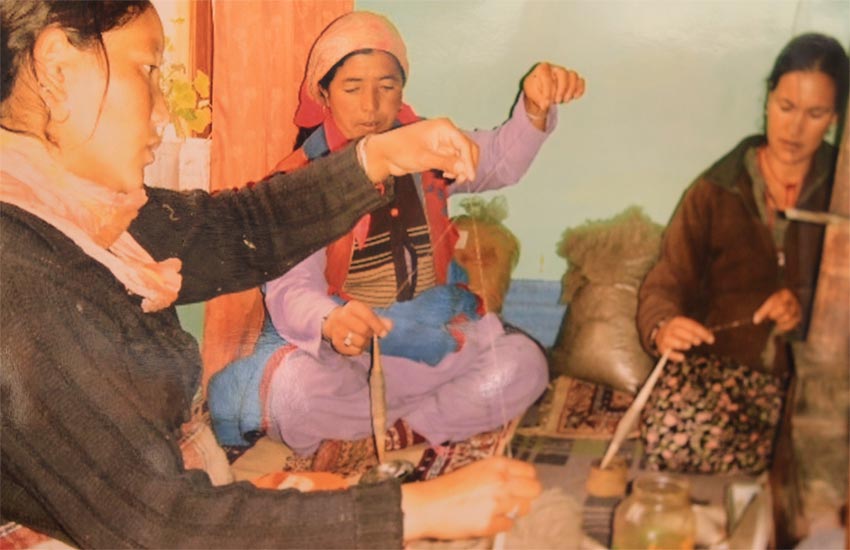

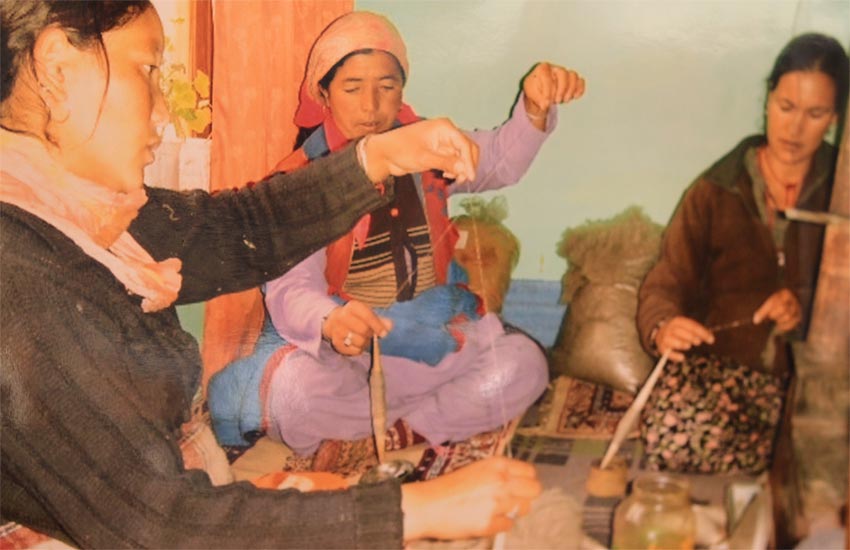

About 500 quintals of raw pashmina is sheared from pashmina goats annually. The sheared one kg of pashmina gives 50% pure pashmina and the 50% is the coarse hair. Once the coarse hair is removed the sorted pashmina is carded by hand to make suitable for spinning. The spinning is done on wooden spindles called ‘phang’, which is now replaced by the ‘Charkha’. The pashmina shawls woven in Ladakh are coarse as compared to pashmina shawl woven in Kashmir.

Normally, it took three complete days for one person to complete one pure pashmina shawl.

The cleaning is still done by hand, after which the wool is carded and spun, again by hand, into two-ply yarn. Women in private homes do both the cleaning and the spinning. It can take nearly a week to turn the ‘pashm’ from one goat into yarn, and it takes about three goats to produce the wool for one standard-size shawl measuring two meters by one meter (78 x 39″). What makes these shawls superior is not only the fineness of the individual pashm fibres, but also meticulous cleaning, sorting, de-hairing and hand spinning. These are all manual skills, perfected by Kashmiri women and passed down through generations since the late 16th century, the time when the Mughal emperors began to encourage the shawl industry.

The weaving of Pashmina shawls involves a few distinct steps:

Fibre Harvesting: Raw Pashmina is collected during spring moulting season when animals naturally shed their undercoat. On the basis of weather conditions and region, the goats start moulting over a period from February to late May. In Ladakh, combing is the major method of harvesting pashmina using a special type of comb. After harvesting, pashmina is dusted manually to remove adhered impurities like sand, dust etc. The fleece is also sorted based on its colour. The natural colours of the fibres are white, grey mixed with brown and brown. Generally, fibres with long fibre lengths fetch a higher price since longer fibres are easier to spin.

De-Hairing: De-hairing is the process by which the outer coat of guard hair is separated from the undercoat fine fibres. Raw pashmina has 50-60% guard hair. The guard hair is very thick 50-100 micron diameter. The guard hair should be removed completely before processing for improving the spin-ability and the development of fine quality pashmina fabrics. The presence of more than 5% guard hair would definitely affect the appearance, handle and quality of the final product. The de-hairing process in Ladakh is carried out manually, followed by teasing on wooden combs. The process is time consuming and laborious.

Sourcing and Bleaching: Pashmina fibre contains about 5% contaminants like wax, skin flakes, suint and dirt. Traditionally, in India, scouring is not done at fibre stage but is carried out in yarn stage before dyeing and weaving The scouring is done by using 0.2 gpl non-ionic detergent at 50 degree Celsius for 10 minutes. The other impurities like burrs and vegetable matters are removed manually. Generally, the process of carbonization, used in wool to remove vegetable matters, is not carried out, as pashmina is very delicate and it might damage the fibre.

Bleaching is not normally carried out for pashmina in India. However, for white fibres or fabrics to be dyed with pale shades, bleaching is required. In such cases, bleaching with hydrogen peroxide is used under mild alkaline condition.

Spinning: On account of small availability of this speciality fibre, most of it is utilized locally with the help of specially designed manually operated traditional charkha locally known as ‘yander’. Combed pashmina is obtained in the form of a loaf called ‘Tumb’ followed by gluing, usually with soaked powdered rice. The yarn can by spun up to 108 Nm.

Weaving: Traditionally, pashmina yarn is wound on a small flange bobbin manually using parota. The size of yarn is done the form of hanks using Saresh as an adhesive to improve strength and weave-ability of yarn. The warping of yarn is carried out manually using sticks. The process is time consuming ad creates non-uniform tension during the weaving.

The weaving of pashmina yarn into shawl is carried out in a special type of handloom. Before weaving, the pashmina yarn is sized with a special type of starch/resin. Skilled artisans usually do the handloom weaving of pashmina shawls. The weight of the hand woven shawl is approximately 200 gm. The end and picks per inch of a pashmina shawl are generally kept between 50-60 and 45-56 respectively. The fabric weight (GSM) is kept at 50-70 gm.

After weaving, the fabric is hand massaged for releasing stress inserted during spinning and weaving.

Dyeing and Finishing: The dyeing behaviour of pashmina is identical with sheep wool. Pashmina fabrics/yarns are also dyed using natural dyes obtained from different sources. The dyers are using indigo for blue colour, annota seed for getting red colour and henna, myrobolan etc. for getting yellow and brown shades. They are also using mordents like aluminium sulphate and ferrous sulphate for getting bright yellow and grey shades respectively.

Pashmina products have a unique softness property along with lustre. Therefore, normally it does not require any finishing process. The addition of any type of finishing agent may spoil the unique softness of the product. However, nowadays, the pashmina fabrics are produced out of machine spun yarn in blends with other fibres. Such blended pashmina products are treated with thermoplastic softening agents like silicone softener, Nano-based softening agents etc. in order to improve the handle.

The other important finishing techniques carried out on pashmina fabrics by few dyers include anti-moth finishing and aroma finishing. Anti-moth chemical such as Eulon is added during dyeing under acidic conditions. The aroma finishing is done by using commercially available fragrance micro-capsules.

Waste:

The only waste generated from pashmina weaving is if the de-hairing goes wrong and the guard hair would occupy most of the pashm. This could happen for a variety of reasons, since the de-hairing in Ladakh is still done manually and it requires being very accurate for the shawl to come out of the same or better quality than expected.

Cluster Name: Leh

Introduction:

Much beloved by India travellers, predominantly Tibetan-Buddhist Ladakh is a beautiful, high altitude area of mountain desert that takes the onlooker on an experiential journey of untouched silence, hidden mysteries and heaven on earth.

District / State

Leh / Jammu and Kashmir

Population

Language

Ladakhi,Tibetan,Urdu,Balti,English,Hindi

Best time to visit

April-October

Stay at

Local hotels, Homestays, Camps

How to reach

Delhi-Leh, Srinagar-Leh, Manali-Leh

Local travel

Mini-Buses, Taxis, Jeeps, Motor-cycles, Cycles

Must eat

Tibetan cusine

History:

The region of Ladakh once formed part of the erstwhile Kingdom of Ladakh and for nearly 900 years from the middle of the 10th century existed as an independent kingdom. Its dynasties descended from the king of old Tibet. After 1531, the Muslims from Kashmir periodically attacked it, until it was finally annexed to Kashmir in the mid 19th century. The early colonizers of Ladakh included the Indo-Aryan Mons from across the Himalayan range, the Darads from the extreme western Himalayas, and the nomads from the Tibetan highlands. While Mons are believed to have carried north-Indian Buddhism to these highland valleys, the Darads and Baltis of the lower Indus Valley are credited with the introduction of farming and the Tibetans with the tradition of herding. Its valleys, by virtue of their contiguity with Kashmir, Kishtwar and Kulu, served as the initial receptacles of successive ethnic and cultural waves emanating from across the Great Himalayan range.

Its political fortunes flowed over the centuries, and the kingdom, was at its best in the early 17th century under the famous king Sengge Namgyal, whose rule extended across Spiti and western Tibet up to the Mayumla beyond the sacred sites of Mount Kailash and Lake Mansarovar. During this period Ladakh became recognized as the best trade route between the Punjab and Central Asia. The merchants and pilgrims who made up the majority of travellers during this period of time, travelled on foot or horseback, taking about 16 days to reach Srinagar, although the people riding non-stop and with changes of horse all along the route, could do it in as little as three days. These merchants who deal in textiles and spices, raw silk and carpets, dyestuffs and narcotics, transported their goods on pony who took about two months to carry them from Amritsar to the Central Asian towns of Yarkand and Knotan. On this long route, Leh was the halfway house, and developed into a bustling Centerport, its bazaars thronged with merchants from far countries. This was before the wheel as a means of transport was introduced into Ladakh, which happened only when the Srinagar-Leh motor-road was constructed as recently as the early 1960s. The 434 km Srinagar-Leh highway follows the historic trade route, thus giving travellers a glimpse of villages that are historically and culturally important. The famous pashm (better known as cashmere) was produced in the high altitudes of eastern Ladakh and western Tibet and transported thorough Leh to Srinagar where skilled artisans transformed it into shawls which are known all over the world for their softness and warmth. Ironically, it was this lucrative trade, which finally spelt the doom of the independent kingdom. It attracted the covetous gaze of Gulab Singh, the ruler of Jammu in the early 19th century, and in 1834, he sent his general Zorawar Singh to invade Ladakh. Hence, followed a decade of war and turmoil, which ended with the emergence of the British as the paramount power in north India. Ladakh, together with the neighboring province of Baltistan, was incorporated into the newly created State of Jammu & Kashmir. Just over a century later, this union was disturbed by the partition of India, Baltistan becoming part of Pakistan, while Ladakh remained in India as part of the State of Jammu and Kashmir.

Geography:

Ladakh has an area of approx. 98,000 sq. km., situated at an altitude of 2,500 to 4,500 meters with some of the passes at 6,000 and peaks up to 7,500 meter all around the region. The four mountain ranges of Great Himalayan, Zanskar, Ladakh and Karakoram pass through the region of Ladakh. Ladakh also has the world's largest glaciers outside the poles. The towns and villages occur along the river valleys of the Indus and its tributaries, Zanskar, Shingo and Shyok. There is also the large beautiful lake Pangong Tso, which is 150 km long, and 4 km wide at a height of 4,000 m. Due to necessity and adverse conditions people of Ladakh have learnt to irrigate their fields. In the fields barley is the main crop, which is turned into tsampa after roasting and grinding. Apple and apricots trees are also grown with success. Most of the crops are reserved for the hard wintertime. At lower altitudes, grape, mulberry and walnut are grown. The willow and poplar grow in abundance and provide fuel and timber, especially during the winter. These trees are also the source of the material for basket making.

By Road: Travel by road gives you an advantage over flying into Leh as it enables you to acclimatize easily. As Leh is situated on a high altitude plateau and travelling by Jeep or car will give you the flexibility of stopping to see the several sights on the way. Srinagar - Leh road (434 km) is the main route with an overnight halt at Kargil. The road is open between mid June and November. The Manali-Leh highway is a spectacular journey with an overnight halt at tented camps at Sarchu or Pang. Kargil is situated on the main highway between Srinagar and Leh. The road from Kargil into the Suru and Zanskar valleys is open only between July and October.

By Air: Leh is the main airport for this area. Direct flights link it to Delhi, Srinagar and Jammu.

Environment:

In peak winters the temperature in Ladakh goes down to -30 Degree Celsius in Leh and Kargil and - 50 Degree Celsius in Drass. Temperatures remain in minus for almost 3 months from December to the month of February. But on clear sunny days it can become very hot and one can get sun burnt. Rainfall is very less due to the geographical location of Ladakh. The rainfall is around 50 mm annually. It is the melting snow, which makes the survival of human and animals, possible. In the desert like landscape one may come across the dunes or perhaps occasionally to the dust storms.

Infrastructure:

Although, most of the places in Ladakh are more or less cut off for 6 months from rest of the world, the state has retained cultural links with its neighboring regions in Himachal Pradesh, Kashmir, Tibet and Central Asia and also traded in valuable Pashmina, carpets, apricots, tea, and small amounts of salt, boraz, sulphur, pearls and metals. Yaks, ponies, Bactrian camels and hunia sheep with broad backs provided animal transportation. Livestock is a precious contribution to the economy of Ladakh, especially the yaks and goats play an important role. Yak provides meat, milk for butter, hair and hide for tents, boots, ropes, horns for agricultural tools and dung for fuel thus paying the most vital role in the local economy of the region. Goats, especially in the eastern region, produce fine pashmina for export. The Zanskar pony is considered fast and strong and therefore used for transport and for the special and famous game of Ladakhi polo. Ladakh is open to tourists only since 1974 and has attracted already a large number of tourists and the influence of the tourists does not remain unnoticed on the society as a large number of people, especially in the capital Leh has to do directly or indirectly with the tourists.

Architecture:

The development of Leh town probably began with the reign of the famous King Sengge Namgyal who ruled in the 17th century and during whose reign the kingdom expanded to its fullest extent. His most visible contribution to the town was the nine-storeyed palaces, which still dominate it today. The area around the palace developed with the houses of several noblemen and residences and temples belonging to different monasteries dotted along the slopes of the hill. The city of Leh traditionally comprised of many ancient localities known as Skyangos Gogsum, Chhubi Yangrtse, Kharyok and Stagofilok. The present city has evolved from some of these ancient localities. Many of the houses and monasteries are built on elevated, sunny sites facing the south, and are often constructed from a mixture of rocks, wood, cement and earth.

The architecture of the historic core uses the same indigenous materials that are used in other traditional buildings of this region. These are sun-dried mud bricks and stone, which have been used with great skill by the local masons to create buildings that have survived several centuries. The layout of the old town, with its narrow alleys and lanes surrounded by ancient adobe structures, gives a rare glimpse of the town's past. The central area of Ladakh has the greatest concentration of major Buddhist monasteries or gompas. Many of these monasteries were built in the past under the direct patronage of members of the ruling Namgyal dynasty. The monastic architectural tradition of this region reflects the underlying principles and approach of Buddhism. The monasteries are situated on the isolated hillock in the vicinity of villages. The monasteries are the focal point of religious faith for the highly religious Buddhist people. Monasteries are the places of worship, isolated meditation and religious instruction for the young. The approach to the monasteries is lined with mane walls and chortens. Mane walls are made of votive stones on which prayers and holy figures are inscribed, while chortens are semi-religious shrines or reliquaries containing relics of holy people or scripts. Today Leh is developing as a major urbanized city and is expanding towards Choglamsar along the Leh-Manali road and towards Phyang on the Leh-Srinagar National Highway.

Culture:

Ceremonial and public events are accompanied by the characteristic music of 'Surna' and 'Daman' (Oboe and drum), originally introduced into Ladakh from Muslim Baltistan, but now played only by Buddhist musicians known as "Mons". The first year of childbirth is marked by celebrations at different intervals of time, Beginning with a function held after 15 days, then after one month, and then again at the end of year. All relatives, neighbors and friends are invited and served with 'Tsampa', butter and sugar, along with tea by the family in which the child is born.

Many of the annual festivals of the Gompas in Ladakh takes place in winter, which is a relatively idle time for majority of the people. It is time when the whole village gathers together. Stalls are erected and goods of daily need and enjoyment are sold. Eatables are brought along and families and relatives would enjoy the meals together. The whole activity takes place around the gompas. In the courtyards of the Gompas, colourful masked dances and dance-dramas are performed. Lamas, dressed in colourful robes and wearing startlingly frightful masks, perform mimes symbolizing various aspects of the religion such as the progress of the individual soul and its purification or the triumph of good over evil. Local people flock from near and far to these events and the spiritual benefits they get are no doubt heightened by their enjoyment of the party atmosphere. This is also an occasion to demonstrate the cultural heritage as well as the wealth of that particular monastery. Big and rare musical instruments, old weapons and religious objects including Thangkas are brought out during the performances. The first ceremony of any festival is very interesting as the male Lama is accompanied by the monks. Musicians, dancers and singers in a harmony create for visitors an unforgettable experience. Some of the popular themes include the victory of good over evil or some special stories related to great Lamas where their supernatural power is demonstrated or the stories related to Guru Padmasambhava. Their dances are also very colourful. A clown plays an important role so that an overdose of religion or history does not disinterest the villagers so that atmosphere is joyful. Spituk, Stok, Thikse, Chemrey and Matho have their festivals in winter, between November and March. There are some festivals, which are celebrated in warmer months. These are Lamayuru Festival (April or May), Phyang Festival, Thikse Festival (July or August).

People:

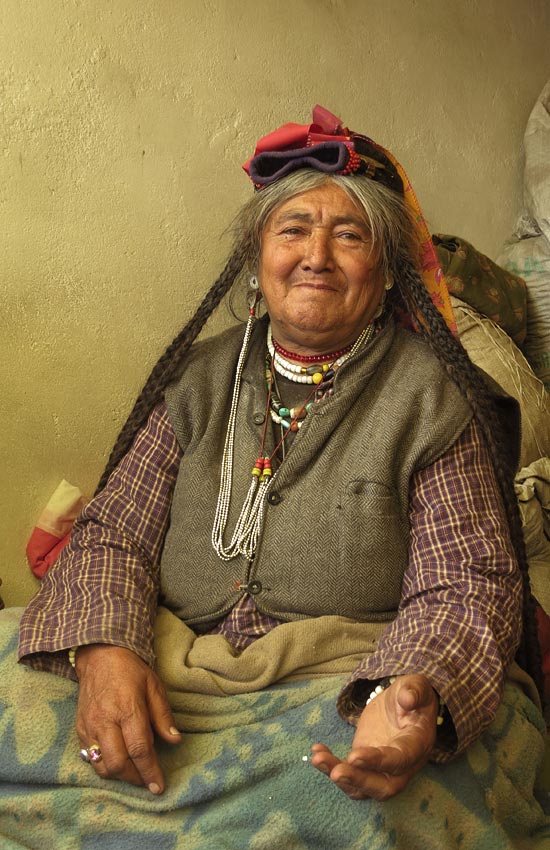

The faces and physique of the Ladakhis, and the clothes they wear, are more akin to those of Tibet and Central Asia than of India. The people of Ladakh are predominantly Buddhist and practice Mahayana Buddhism influenced with the old Bon animistic faith and Tantric Hinduism. Bon religion and Tantrism involved rituals to fulfill the wishes and so they were very popular before Mahayana Buddhism dominated.

'Arghon', is a community of Muslims in Leh who are the descendants of marriages between local women and Kashmiri or Central Asian merchants. There are four main groups of people. The Mons who are of Aryan stock are usually professional entertainers, often musicians. The Dards are found along the Indus valley, many converted to Islam, though some remained Buddhist. Tibetans form the bulk of the population in Central and Eastern Ladakh, though they have assumed the Ladakhi identity over generations. The Baltis, who are thought to have originated in Central Asia, mostly live in the Kargil region. The Ladakhis are cheerful and live close to nature. The Ladakhis wore the goncha which is a loose woollen robe tied at the waist with a wide coloured band. Buddhists usually wear dark red while Muslims and nomadic tribes often use undyed material.

Famous For:

Hemis Festival in Ladakh: Hemis is the biggest and most famous of the monastic festivals, frequented by tourists and local alike. Hemis Festival is celebrated in the end of June or in early July and is dedicated to Guru Padmasambhava. After every 12 years, the Gompa's greatest treasure, a huge thangka or a religious icon painted or embroidered on cloth is ritually exhibited.

Tak-Tok Festival in Ladakh: Tak-Tok festival is celebrated at cave Gompa of Tak-Tok in Ladakh. It is one of the major festivals of Ladakh. Tak-Tok festival is celebrated for about ten days after Phyang festival. This festival is celebrated in summer, and yet another tourist attraction. The festival is celebrated with fanfare and locals from far areas storm the place on the occasion.

Sindhu Darshan Festival in Ladakh: Sindhu Darshan Festival, as the name suggests, is a celebration of the Sindhu River. The people travel here for the Darshan and Puja of the River Sindhu (Indus), which originates from the Mansarovar in Tibet. The festival aims at projecting the Sindhu River as a symbol of multi-dimensional cultural identity, communal harmony and peaceful co-existence in India.

Craftsmen

List of craftsmen.

Documentation by:

Team Gaatha

Process Reference:

Cluster Reference:

http://www.ladakh-tourism.net/Ladakh_Information.htmhttp://www.ihcn.in/leh/leh/243-planning-and-architecture-.htmlhttp://factsanddetails.com/china/cat6/sub36/item204.htmlhttp://www.rinpoche.com/stories/ladakh.htmhttp://www.lehladakhindia.com/buddhism-in-ladakh/#sthash.B4vTATOG.dpuf